A common motif in Western literature and art is the representation of snakes as the embodiment of evil and deceit. We could ask ourselves, as Indiana Jones usually does on one of his adventures, “why’d it have to be snakes?” You would be hard-pressed to find a positive portrayal of a serpent in a film or book: In Harry Potter, Voldemort has a pet snake in which he places part of his soul and a dark wizard is identified by his ability to communicate with snakes. The long-running television show Dr. Who depicts a being of pure hatred that survives on fear as the giant snake Mara. In classic stories like the Jungle Book, Kaa the python is always up to something treacherous through use of hypnosis and deceit. And older still, is the famous example in the Book of Genesis, when a serpent seals Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden through cunning trickery.

Countless more examples abound, but why are serpents always linked to evil? Why not sharks, spiders, lions, or bats, all of which tend to instill equal amounts of fear among people and yet don’t have the long-lasting associations with evil like that of snakes? Most species of snake are not particularly vicious or dangerous, at least compared to any other animal that might be associated with evil, and yet it is always snakes.

Historically, snakes have always been a common symbolic motif, and in many early human cultures they did indeed represent evil. Nearly all cosmogonies of early civilizations – origin myths that explained the creation of the world – depicted snakes as evil beings set on world destruction.

- The story of Gilgamesh from early Mesopotamia told how a stole the plant that provides eternal youth, causing Gilgamesh to lose his immortality – a bit like the story of the garden of Eden, where immortality in the garden was lost due to the trickery of a serpent.

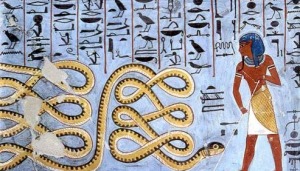

- In Ancient Egypt, Apophis was the serpent that tried to stop the sun god Re from bringing forth morning and thus he had to be battled and conquered every night before the sun could rise again.

- The Vikings believed that Jörmungandr was a serpent so large it could encircle the earth and bite its own tail. It was the serpentine arch-nemesis of Thor that would one day kill him and initiate Ragnarok by squeezing his tail and destroying the world.

And even when they aren’t screwing over all of mankind with plans to destroy the world, snakes are still up to mediocre bouts of evil – in Greek mythology the half-human monster Medusa, who could turn men to stone with a single glance, had snakes for hair. This probably fueled later medieval folklore that warned of a giant serpent called a basilisk, whose gaze rendered its victims dead.

The Basilisk has remained a popular mythical monster, starting in Ancient Greece and continuing on through the Dark Ages, and famously reappearing in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

Although the stealthy behavior and sometimes venomous bite of a snake is part of the natural, biological world, it still gives people reason to dislike them, and the way that they move and slither through grass unseen makes snakes a useful metaphor for a deceitful or sly person. They flick their tongues in and out in a slightly sinister way, therefore having a “serpent’s tongue” makes one untrustworthy. If there is a legitimate reason to fear or dislike something in the physical world, it makes it easier to transfer that fear into a symbol that could represent pure or supernatural evil, because people already have a negative connotation to it.

But in non-Western cultures, snakes aren’t always evil, and sometimes were represented in a duality of good and evil – although Apophis opposed the sun god Re, a Uraeus was a cobra image atop the crown of an Egyptian king meant to protect him. Serpents meant different things to different members of society and different societies as a whole.

The Caduceus of Greek Mythology was the “messenger” staff carried by Hermes and Iris and was wrapped with two winged snakes. In modern times it is sometimes confused with the Rod of Aesculapius – which only had one, un-winged snake. As the god of medicine and healing, Aesculapius and his followers worshiped snakes and products derived from them, especially venom, were thought to have medicinal properties in ancient times.

On the left is Hermes carrying the Caduceus and on the right is Aesculapius carrying the Rod of Aesculapius. Although the Rod of Aesculapius was carried by the god of medicine and healing, the Caduceus is sometimes portrayed in modern times as a symbol of emergency and medical services.

The imagery of a snake shedding its skin and emerging anew has also lead to its representations of rebirth, especially in Hindu cultures. During the festival days of Shravana, the “Nag panchami” involves snake worship in a quest for fame and knowledge. But a snake can also represent sexual desires and passions, both positive and negative, and could therefore contribute to an individuals downfall.

And remember Apophis, whom the Egyptians had to defeat every night? Though a figure of evil, he might not have been truly hated but instead seen as a power to be reckoned with and a necessary part of life. Good cannot triumph over evil if there is none to defeat and the ancient Egyptians valued a balance of good and evil, order and chaos, ma’at and isfet – the world is not balanced if there is no evil and an unbalanced world was seen as the true danger.

Likewise, in Norse belief, there was no avoiding Ragnarok – it was fated to happen, and Thor knew he would die to Jörmungandr long before it would happen. So with this cultural perspective, the serpent may be seen as less of an agent of evil and more as an agent of fate, a messenger that acts to ensure the world carries on as it is meant to, whether this be good or bad for everyone involved.

The definitive imagery as serpents being fully evil didn’t really exist until Christianity came along. It is possible that the early ideas of the duality of snakes – both good and evil – is what sealed the future perceptions of snakes in a negative light. The early Church did not like dualities in ideas and early Christianity usually saw things as all good or all bad, with little middle ground. Dualities left too much open for interpretation by commoners, which was a disadvantage in a time when the Church was trying to spread quickly across cultures and into new territories.

Sadly, it was not uncommon for Christians to vilify the pagan beliefs that they did not adopt, making them wholly evil and therefore more straightforward to the common people. (Even the meanings of the words “vilify” and “villain” come from an early Christian attempt to associate the pagan French “vilain”, simply meaning a peasant farmhand, into something evil because they were, after all, pagan.) Snakes, which represented many ideas of both good and evil, came to be associated with devil worship, sorcery, and deceit because an individual could be deceived by an idea with more than one meaning. Therefore, placing a serpent in the Garden of Eden as the ultimate downfall to mankind and as the form that Satan himself chooses when he tempts Eve, has created a permanent connection between serpents and “evil”, which has lasted for hundreds of years and still persists in Western culture today.